瓦 Kawara – Roof Tiles in Japan

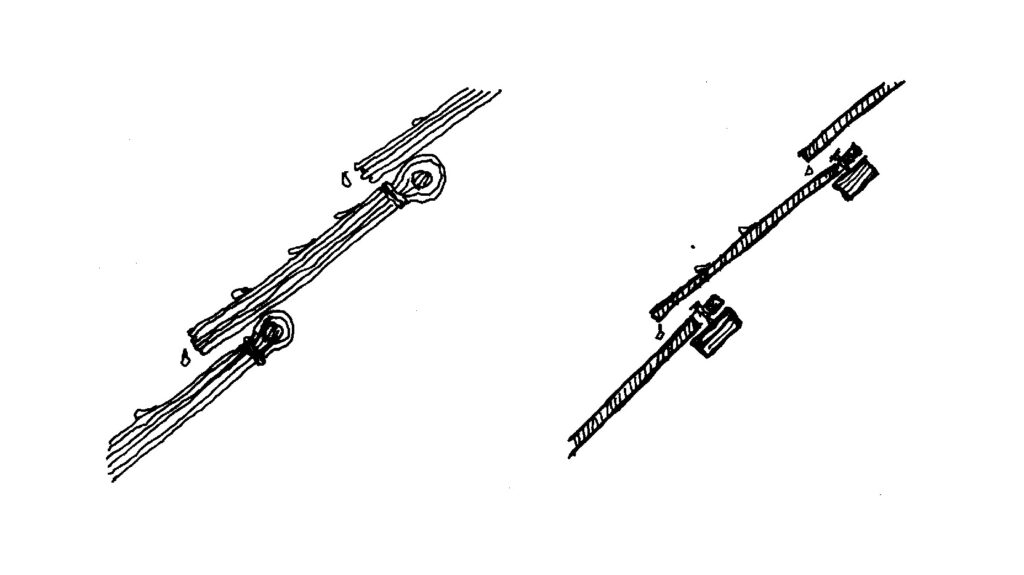

The earliest form of roof construction, thatch, is made by piling up straw, which must be laid at a steep slope, overlapped and be thick enough to shed the rainwater. Replacing the straw with overlapped pieces of cypress bark or clay offers a larger waterproof surface, but there are still joints which must be sealed.

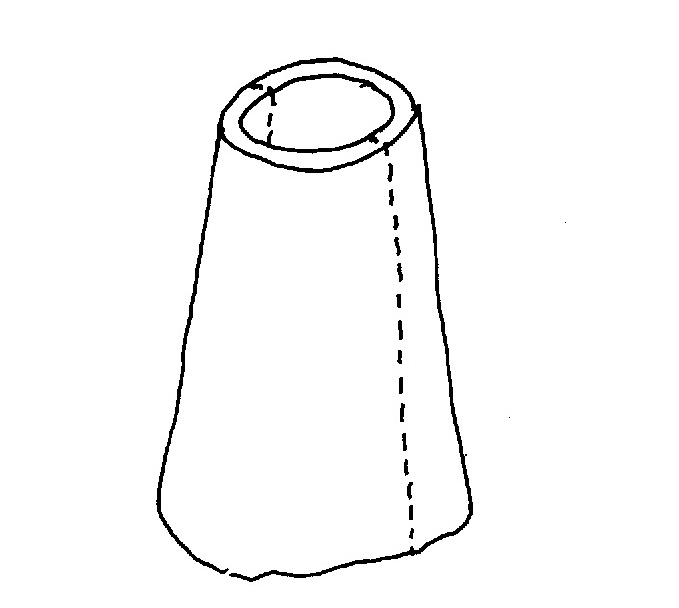

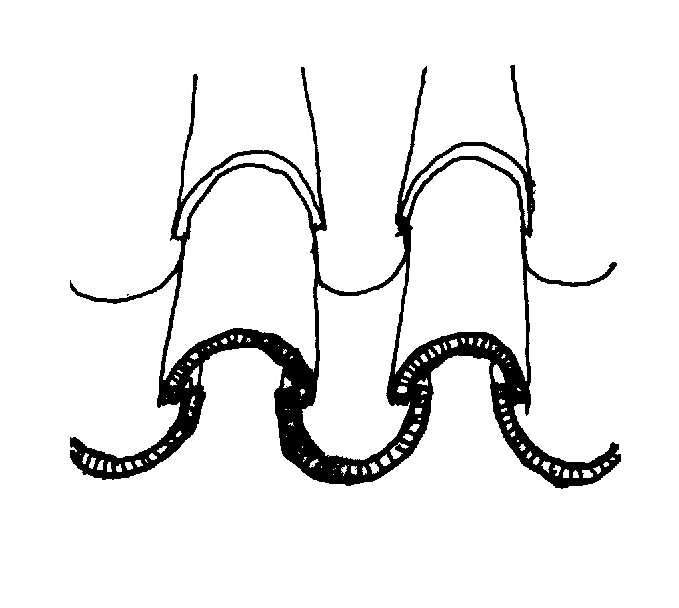

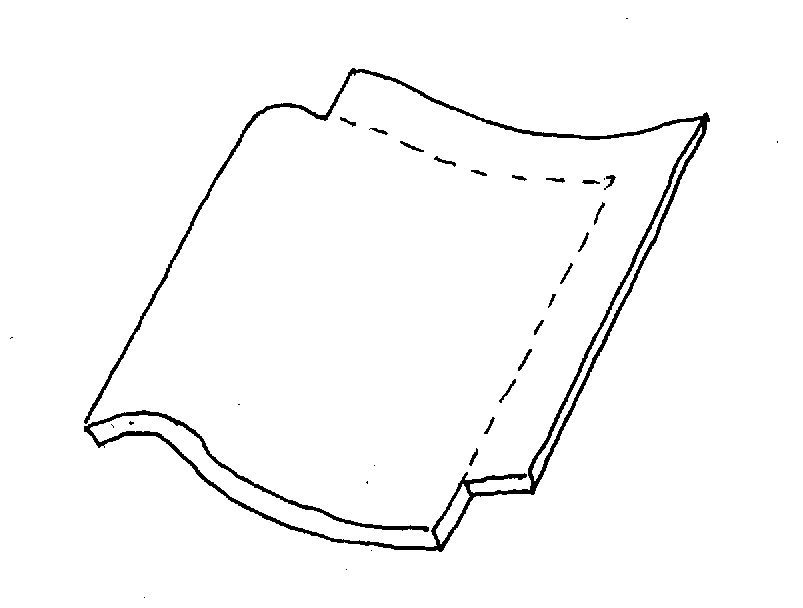

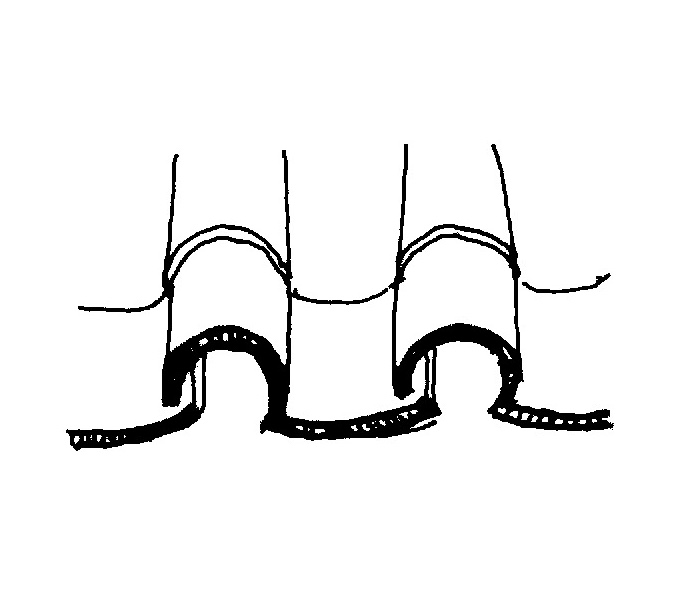

Clay tiles can be formed with a lipped edge, or “pan-tiles” can be made from open-ended pots in a shallow cone shape cut in half. The roof is then laid with alternating rows of upward and downward facing tiles.

Fired clay tiles have been used for thousands of years, but were introduced to Japan in 588 CE, according to the Japan Chronicles (Nihon Shoki), by 4 roof tile experts from the Kingdom of Baekje, in what is now Korea. By this time, Japanese architecture had developed many of its complex and unique forms, so traditional architecture in Japan is still based on thatched roof design, even when the straw has been replaced with tiles. Buddhism was introduced around the same time, and the first Buddhist temples had tiled roofs, starting with Asuka-dera in Nara in 596. The first tiled secular building was Fujiwara Imperial Palace a century later.

Edo era feudal society’s prohibition on luxuries for common people, such as wearing silk or bright colours, also applied to roofing tiles. However, the relatively fire-proof nature of clay was understood and merchants were able to obtain dispensation. Tiled roofs were still relatively expensive, because the building frame had to be stronger to carry the extra weight, and gaps between tiles degraded the fire resistance

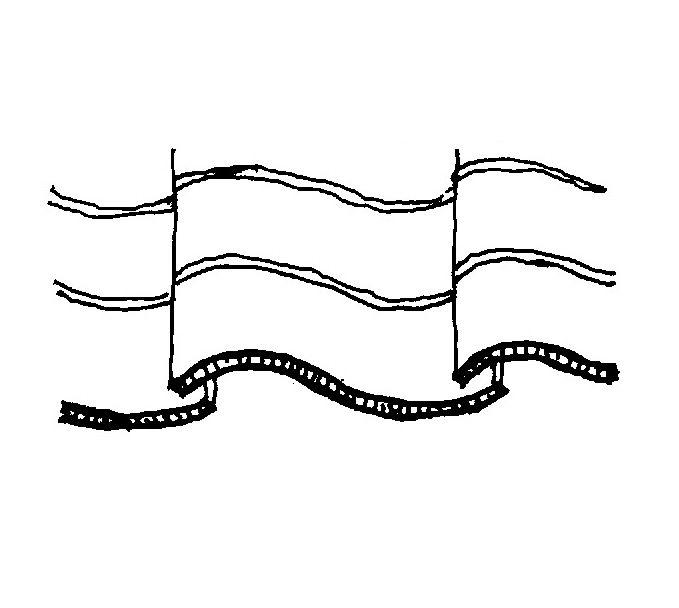

The tile system introduced from Korea, Hongawara, consisted of near-flat tiles combined with almost circular tiles covering the joints. When used in Korea, its dimensional tolerance allows the distinctive and graceful upward-curving roof edges. Even with basically planar roof designs in Japan Hongawara are mainly used for shrine buildings.

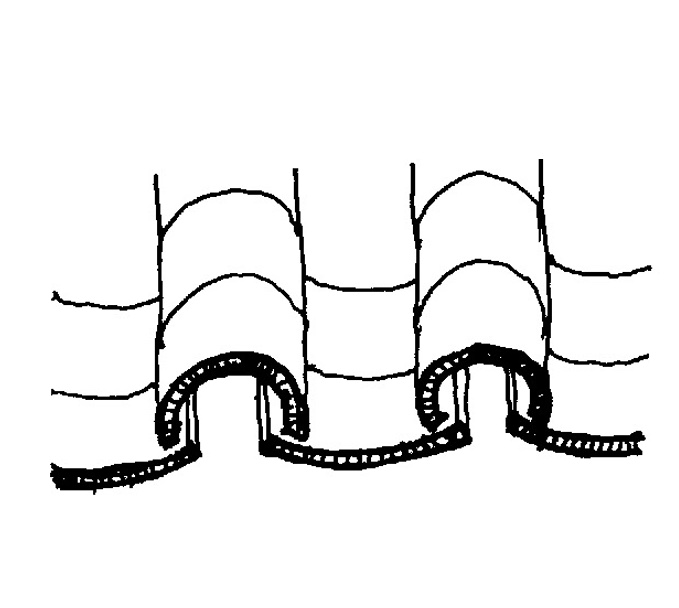

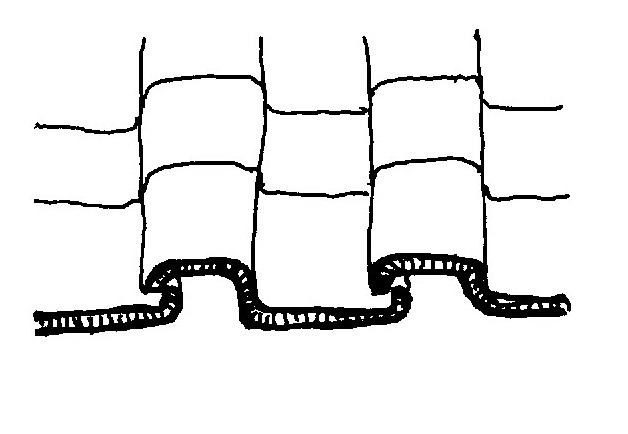

In 1674, Hanbei Nishimura, combined the 2 shapes into a single piece called Sangawara. The resulting moulded tile was less expensive, lighter weight and, with added lipped or hooked edges, could be made more fireproof and earthquake resistant. The design could be adjusted to mimic the traditional Hongawara tiles, form a wave or S-shape or given a more European appearance. Most importantly, its lower cost and light weight make it suitable for domestic construction.

The Sangawara are usually laid left to right, when looking towards the ridge, so the hooked or rounded part is always on the left. Well, mostly. Next time you see a traditional roof, see if you can tell whether it’s Hongawara or Sangawara.

about the Author: I am an architect from the U.K., working in Japan. The symbol at right is my Kamon or identifying mark, representing Mount Fuji surrounded by clouds. It is formed from my initials, A and S. – Andrew Sheppard