Japanese Roofs 日本の屋根

The landscape of Japan is largely mountainous and forested, so it is natural that the earliest buildings were made of wood, with leaves or other plant materials as infill.

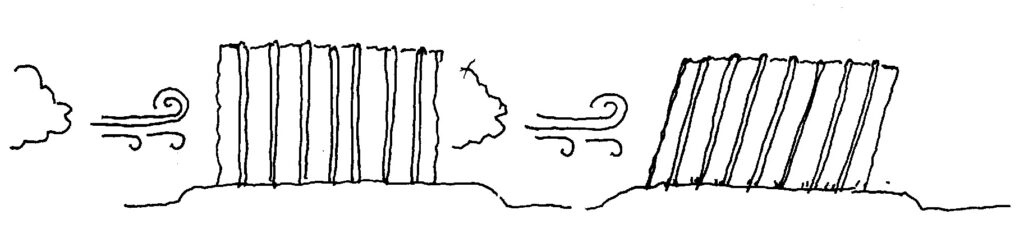

The simplest way of constructing a building is by forming an A-frame with two sets of inclined posts, with horizontal supports carrying a thatch of leaves, straw or bark. There are three practical disadvantages of this primitive form – that a large portion of the structure is unusable by standing humans, and that without additional elements the ends are open. The third problem is that a gable structure is strong and streamlined in resisting wind from the sides, but less so in the direction of the ridge, when the structure is subject to “racking”, and the rectangular space between frames becomes a parallelogram. A similar distortion occurs when the building is subject to earthquakes.

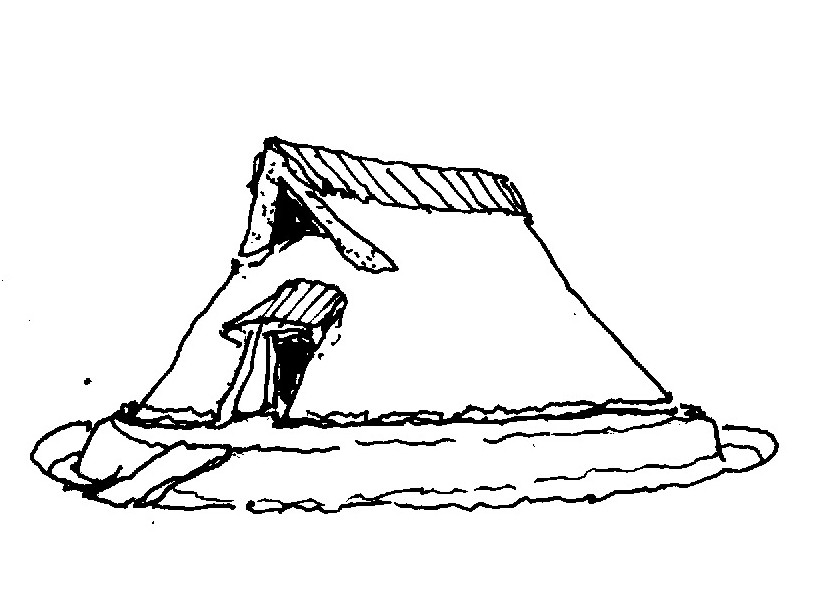

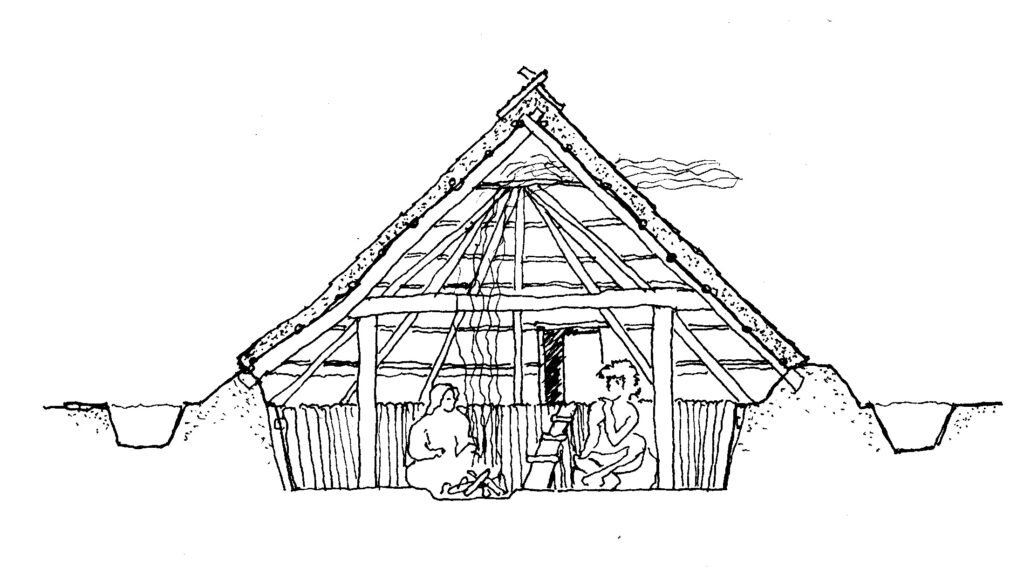

The practical solution to all of these problems was to excavate an area of earth within the roof space, and to make semicircular ends with similar inclined posts, which act as wind bracing and prevent racking. This type of building was developed in many parts of the world and the earliest. buildings in Japan, known as “pit houses” or Tateana Jukyo、竪穴住居, emerged about two thousand years BC. The combination of inclined roofs and semicircular ends created partial gables where these met, allowing an opening which vented smoke from cooking fires. An entrance, with its own protecting roof, could be formed either below the gable or at the side.

Reconstructed buildings of this type can be seen at Tsuyama in Okayama-ken, and on their original footings at Toro no Iseki in Shizuoka.

The cultivation of rice spread across Asia during the Jomon or Stone Age period, and led to settlements of Tateana Jukyo. These buildings had some disadvantages, including vulnerability to animals, insects, floods and theft. They were thus unsuited for the storage of the rice harvest, and this led to the development of a different type of building, by about 300 BC, known as Takayuka Jukyo, 高床住居 or “raised floor houses”.

Elevating the floor against these threats required an additional vertical element, a wall, to support the inclined roof structure. It also created usable space on the lower level. In regions where timber was scarce and stone, mud or clay were available, the wall could be solid and loadbearing, but in Japan, loadbearing timber posts were used. Even if the infill wall was made of wood, it was non-loadbearing, and the posts, combined with the roof structure and hefty horizontal beams, formed a strong earthquake-resistant structure.

Thus traditional architecture developed across Japan, based on wood posts and beams, inclined roof structure and thatched roofs, until 588 CE when, according to the Japan Chronicles (Nihon Shoki), four travellers from the Kingdom of Baekje, in what is now Korea, introduced clay tiles to Japan.

The official record does not explain whether the roof experts’ main purpose was to introduce Buddhism and the tiles were secondary, or that a Buddhist temple, with its more centralized plan, was a good example of the use of clay tiles. Either way, Japan’s first Buddhist temples had tiled roofs, starting with Asuka-dera in Nara in 596. The first tiled secular building was Fujiwara Imperial Palace a century later.

By this time, Japanese architecture had developed many of its complex and unique forms, so traditional architecture in Japan is still based on thatched roof design, even when the straw has been replaced with tiles.

More on the architectural forms of Japanese roofs in Part 2