Japanese Roofs 日本の屋根 part 2

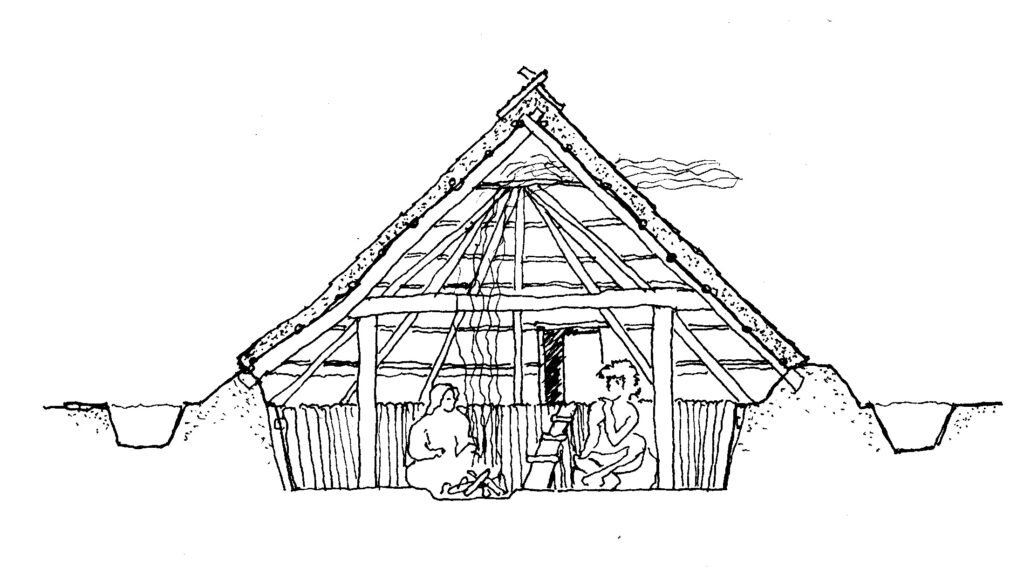

Part 1 of this series described a rustic A-frame house, with inclined poles carrying a thatched roof, with a partially-excavated floor and semicircular ends. The original stone age dwellings would have been like this, but the illustration included an additional element – a frame of four massive vertical posts with their tops joined by beams. These timbers allowed the construction of a much larger house, with the beams supporting the mid-point of the roof timbers.

Evidence of the smaller buildings might have been obliterated, while the distinctive post holes are clearly seen in the archaeological remains, so reconstructions such as at Toro no Iseki in Shizuoka are based on the larger framed structures.

As civilization developed people learned to cultivate rice, and Part 1 also described a variation of the building type, with the roof and floor separated from the ground, that provided a storage space to protect the rice harvest from rain, theft and animals.

The stone age house would have been occupied by an extended family or clan group, but a rice-cultivating society would need a larger building for a communal gathering. The storage building form could be more easily adapted, and improved carpentry skills led to the development of tall and complex roof trusses that could span a much wider space. Surrounding this wide space with a narrower span allowed a paired structure to resist the spreading force of a heavy roof. It also makes construction easier as the surrounding structure can be made self-supporting before the main roof is begun.

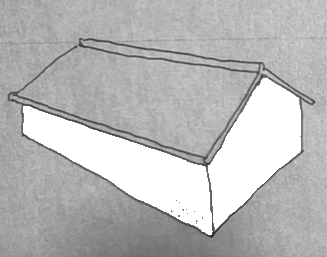

A simple roof with this form in a straight line has a triangular shape at each end called a gable. This style is called cut-off roof or kirizuma yane 切妻屋根in Japanese. With a steep pitch for a thatched roof, the gable wall is more than twice the height of the side walls, and with wood construction you can often see a representation of the internal structure on the outside of the building, used to strengthen the gable wall.

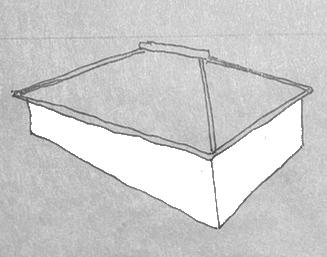

As with the stone-age structure, the simple gable needs strengthening to resist wind forces and to stop the structure from racking. A simple way to do this is to carry the roof detail around the corner with a 45˚ hip. The hip-roof style is called yosemune zukuri 寄せ棟造り.

These two ways of building a roof are both fairly simple, each having advantages and disadvantages. Perhaps the biggest disadvantage of the hip roof, especially when used with thatch, is the three-way junction at the ridge.

Tiled roofs depend on purpose-made tiles to prevent rain penetration at the junctions. Thatched roofs can also use these, but before tiles were introduced they depended on making the thatch thick enough, and adding heavy wooden or stone elements to prevent the thatch blowing away.

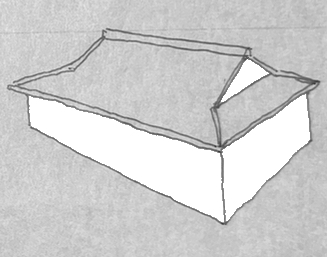

The Japanese combined the two forms, gable roof and hipped roof, extending the ridge to avoid the three-way junction and exposing a smaller gable above the hipped portion of roof. This hip and gable roof style is called irimoya zukuri 入母屋造り.The result is reminiscent of the open gable of the stone age house smoke vents seen at Toro no Iseki. It also has a more imposing appearance than either gable or hipped roofs.

Considering that most aspects of architecture in Japan, including tiled roofs, originate from China, why is this style particularly Japanese?

There are examples of combined hips and gables in China, but their appearance is often merely decorative, and their proportions seem strange. This is because Chinese buildings are based on brick walls, while buildings in Japan are based on timber construction. For one thing, it is not easy to build a solid brick wall high up in the roof structure. Also, if the roof detail is carried around the corner, it is desirable to use a regular building module.

For example, if the building has columns at a spacing of 3 metres, this is enough for a generous corridor or a small ante-room at the outside of the main space, so it would make sense to use this module on all four sides of the building. There is a preference for an odd number of modules, to allow a central entrance. A small building may therefore be 5 x 7 modules. A good place for the gable would be directly above the inner column line. This would make the gable portion of the roof 1.5 times the height of the hip portion, enough to seem imposing but not overwhelming. The hip portion is also large enough to stabilise the roof structure.

Thus, while western architecture discovered both gable and hipped roofs, and in ancient Greece made a huge statement in gables, the Japanese not only made both, but were able to combine the two simple forms into a unique version that was inherently more complex than either. That combination, however, made construction easier, was more able to resist the lateral forces of earthquakes and typhoons and provided an imposing but harmonious aesthetic that is unique to Japan.